Link to the original article

PDF version of the article

Professor, international team receive $34.3 million grant

The Michigan Daily

Published June 4, 2019

A team of international scientists secured a $34.3 million, seven-year grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for their international research on influenza, commonly known as the flu. The team includes Aubree Gordon, University of Michigan assistant professor of epidemiology, and Paul Thomas, professor at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Gordon said her group’s research could provide more data to create better flu vaccines and lead to new insights into immune system responses.

“I was incredibly excited, and it took a little while to sink in,” Gordon said. “I think vaccines are one of the best tools that we have to improve global health. I think this grant in particular may have broader impacts as I think it will provide insight into the development of the immune system in addition to our influenza-specific findings.”

The seven-year observational study will consist of a team of international experts in immunology and virology, two new cohorts in California and New Zealand and one existing cohort in Nicaragua. Each location has different flu seasons and vaccination rates, with rates being highest in Los Angeles and lowest in Nicaragua. Gordon believes each area may have different strains of influenza, so the vaccines may be different.

The three locations could help determine if immunity is affected by different flu seasons in different hemispheres.

“We think these seasonal patterns might actually impact immunity,” Gordon said. “So, if we see the same thing across multiple populations, then that’s really going to strengthen the finding that it’s not specific to some epidemiologic situation that was set up in that country.

At each location, the group plans to enroll children at birth and then follow their immune response history to influenza antigens from either vaccination or infection. The data could explain how the immune system develops, its response to influenza and how one’s first exposure impacts future responses to the virus. These mechanisms, Gordon says, are still unknown to the scientific community.

The grant is called the Dissection of Influenza Vaccination and Infection for Childhood Immunity and classified by the National Institutes of Health — the parent organization of the NIAID — as an U01 or research project grant. Gordon said if the team had received an R01 grant instead, they would have only been able to do basic parts of the study.

The NIAID also awarded a similar grant to Mary A. Staat, a professor at Cinicinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

The team of scientists plan to use a large portion of the grant money to maintain and form the cohorts and international team of immunologists. Her group specifically will coordinate with the University data management center to analyze data.

In an email to The Daily, Thomas wrote large studies like this one could answer many questions regarding human immunity.

“Longitudinal cohort studies are incredibly powerful for determining principles of human immunity,” Thomas wrote. “There have not been many opportunities to fund these types of cohorts, and almost none that would fund infant cohorts on this scale.”

In addition, Thomas said the grant will also allow them to collaborate with a large team and discover better vaccines.

“Combined with the expert team we were able to assemble, the impact on my work is that it provides an unprecedented opportunity to make new discoveries into how the immune response to influenza develops and how childhood immunity against pathogens works in a general sense,” Thomas wrote. “Determining how a successful immune response works against influenza in young children may help inform the design of better vaccines.”

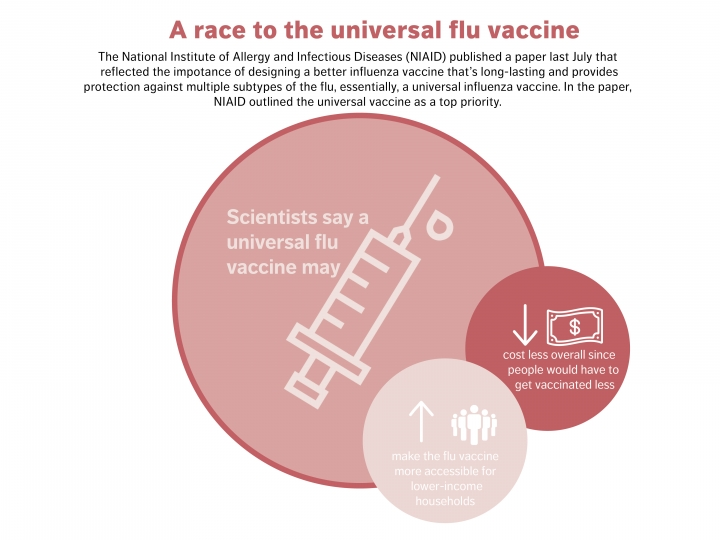

Rackham student Steph Wraith, who works with Gordon, mentioned a paper published by the NIAID last July that reflected the importance of designing a better influenza vaccine that provides protection against multiple subtypes of the virus — essentially, a universal influenza vaccine. In the paper, the NIAID outlined the universal vaccine as a top priority, which Wraith said the team used to drive their work.

“It’s basically an idea of a vaccine that provides … a more robust, long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of flu, rather than a select couple of strains,” she said. “It would basically be eliminating that need to kind of update and re-administer what we have right now, which is a seasonal flu vaccine that has to be readministered every year.”

Wraith said, although there’s been a big measles outbreak due to what she deems as misinformation about vaccines, she is relieved to see the influenza vaccine hasn’t been under as much fire. Even though people will have to receive seasonal flu vaccines every flu season, Wraith said she believes the research could better explain the immune system response.

She said she hopes a future universal influenza vaccine may convince more parents to vaccinate their children, because she thinks it would be effective for longer periods of time.

“(I hope) we can kind of better tailor the vaccine in such a way that maybe we can target it towards areas that aren’t mutating as rapidly on a year-to-year basis,” Wraith said. “So maybe you’re only getting the flu vaccine every couple of years. Already that’s going to make it more likely that people are going to get it on a regular basis.”

Gordon agreed with Wraith, and added she would like to see a vaccine that not only protects for longer but is also more affordable for parents in countries with low vaccination rates like Nicaragua.

“The current seasonal flu vaccine you have to get every year for protection, and in low and middle income countries … it’s not feasible to use a vaccine that costs that you have to deliver every year,” Gordon said. “I’d like to see something closer to natural immunity, where people are protected for longer.”

Both Gordon and Wraith hope to further Thomas Francis Jr.’s work. Francis, a virologist and epidemiologist at the School of Public Health, was the first U.S. scientist to isolate the influenza virus in the 1930s. In his paper published in 1960, titled On the Doctrine of Original Antigenic Sin, Francis argued one’s past flu exposures impact responses to new strains and subsequent influenza exposures.

Wraith said she’s excited to expand on Francis’s ideas, as she’ll be on the project for a minimum of two additional years.

“It’s kind of exciting to, almost 60 years later … really (be) building on those ideas that started here at Michigan,” Wraith said. “Being able to expand on them and build on them and, hopefully, move in the direction of enhanced protection against influenza.”

Daily news reporter Michal Ruprecht can be reached at mrup@michigandaily.com.

Return to clips