Link to the original article

PDF version of the article

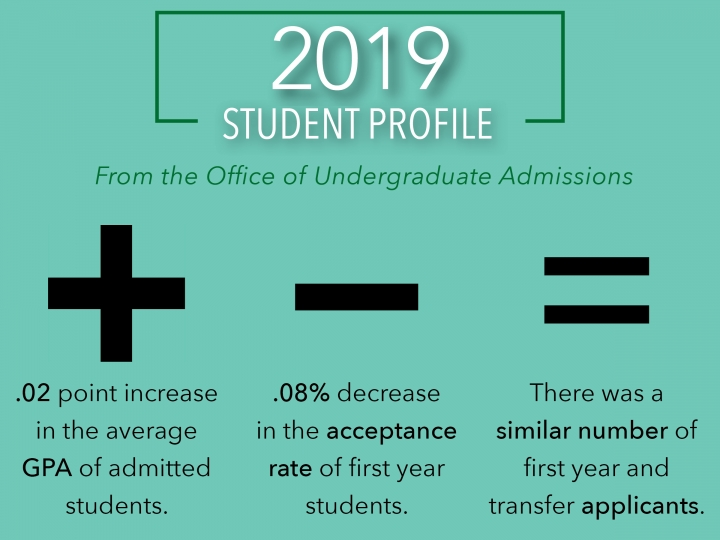

First-year admissions more selective, early numbers show

The Michigan Daily

Published Aug. 9, 2019

Early numbers from the University of Michigan Office of Undergraduate Admissions show a lower first-year acceptance rate and stronger ACT and grade point average scores compared to last year’s admitted students.

The first-year acceptance rate decreased by 0.08 percent, while the transfer student acceptance rate increased by 3.3 percent and the number of transfer applications decreased from last year. The admitted students’ average GPA rose by 0.02 points and ACT test scores rose by one point in the middle 50th percentile ACT score range, while the SAT test scores see no noticeable change.

LSA freshman Sukainah Khan wrote in an email to The Daily she believes high test scores and the increasingly competitive college process correlate with the use of prep books and tutors, which are primarily available to higher-income students.

“Increasing test scores definitely indicates an upward trend in academic excellence and competitiveness, but it also brings a certain degree of uniformity to the student body,” Khan wrote. “Certain academic results correlate to demographic factors that have contributed to students’ ability to succeed. There’s a reason why a large percentage of the student body at UM comes from high-income families.”

LSA sophomore Isabella Yockey attended Northville High School, a school that regularly sends a high percentage of students to the University. She said the school offers a multitude of resources to keep students on the college track, such as counselors, tutors and representatives from the University.

“At Northville, they took a lot of pride on their SAT and ACT scores,” Yockey said. “They offered a lot of help with raising your scores, in the counseling office they offered a lot of resources to find tutors and go to classes. … We worked really close with our counselors to make sure we were on the right track.”

Yockey said she believes the help Northville offered her gave her an edge when applying to the University. She said she thinks in-state high schools who are unable to offer as many resources may be at a disadvantage from an admissions perspective.

“I think it’s unfair in the sense that the schools don’t have the resources to give their students,” Yockey said. “I think that since (Northville) is a wealthier area, the biggest difference is that we were able to be given those opportunities.”

Business sophomore Ariana Khan agrees with Sukainah Khan, stating in an email to The Daily she believes test-prep classes play an important role in the increase in test scores. To combat this socioeconomic disparities in college applications, Ariana Khan created RealU, a company that gives low-income and first-generation students an opportunity to receive mentorship from a college student.

“Many lower-income and first-generation students did not have the opportunities and access to connections of experienced adults in their field of interest,” Ariana Khan wrote. “For this reason, many of the students feel lost in the application and college search process. We hope to make the college search process as easy as possible to ensure students can enter college confidently.”

Before applying to schools, Sukainah Khan said she conducted a lot of research and found that while personal statement and supplementary essays do play an important role in college admission, test scores seem to be the decisive foundation of the entire application process.

“From what I’ve come to understand, test scores often act as a threshold in the admissions process, especially when considering selective universities,” Sukainah Khan wrote. “Upon reaching this threshold, admission decisions fall to the other components of one’s application, such as personal statements, extracurriculars and supplemental materials. Test scores play a unique role. A good score will not guarantee you admission to a program, but a bad score can certainly raise a red flag, giving reason for your application to be tossed.”

One approach from the state level to resolve the increasing disparity in higher education based on class and wealth is state-funded college admission tests.

During the 2017-18 school year, 10 states, including Michigan and Washington, D.C., funded the SAT, while 19 states funded the ACT, according to U.S. News. A Washington Post article said these state-funded ACT and SAT tests aim to alleviate the disparity between high- and low-income students and gives students a chance to consider college.

According to the College Board website, “the Michigan Department of Education uses the SAT as one part of the Michigan Merit Examination.” The College Board claims they’ll make “it easier for students to get ready for college and their careers.”

In an email to The Daily, senior director of media and public relations for ACT Ed Colby wrote the State of Michigan began to fund the ACT in 2007 until the College Board won a three-year contract in 2016, beating ACT’s proposal. The College Board provided all schools and students with free test prep materials and online practice tests to help students prepare for the redesigned SAT in 2016. After the change, Colby said less Michigan students have taken the ACT.

Colby wrote the ACT assists low-income students by providing fee waivers to take the ACT for free up to two times and send their score to colleges and scholarship agencies for free. He added low-income students are also provided with ACT Online Prep and ACT Rapid Review and all students have free access to ACT Academy.

University spokesman Rick Fitzgerald confirmed in an email to The Daily that about two-thirds of the applicants submitted SAT scores and one third submitted ACT scores in 2019, while 18 percent submit both scores. Fitzgerald acknowledged that state and regional testing policies such as the SAT funding programs in Michigan could account for the difference.

Fitzgerald also emphasized the University uses a holistic review process when examining an applicant’s test scores.

“An applicant’s test score is viewed through the lens of a holistic review process that takes into account the rigor of the curriculum available at an applicant’s school, as well as the curricular choices the applicant has made in their academic career,” Fitzgerald wrote. “As the admissions process continues to be competitive and students submit standardized test scores that are in close alignment with their peers, our evaluators increasingly rely on other aspects of the application to inform their decisions.”

Fitzgerald noted the University will release more specific data on the incoming 2019 class in October, including data on GPA, test scores and demographics.

Despite state and students efforts and the holistic review process Fitzgerald mentioned, prestigious institutions, including the University, seem to remain more accessible to high-income students than to low-income students.

According to a study conducted by the Institute for Higher Education Policy, a 10 percent gap exists between underrepresented minority high school graduation rate in Michigan and the percentage of underrepresented minority students attending the University. In addition, low-come students are 23 percent less likely to get into the University and are seven percent less likely to graduate.

Eleanor Eckerson Peters, Assistant Director of Policy Research at IHEP, wrote in an email to The Daily that the University has multiple policies in place that can be advantageous for higher-income applicants and serve as barriers for their lower-income peers, such as demonstrated interest or legacy status.

Peters also added the University seems to be lacking in diversity both ethnically and socioeconomically in its student population.

“When we conducted our analysis in 2018 U-M Ann Arbor’s enrollment of underrepresented minority students entering the freshman class was only 11 percent, and only 15 percent of the incoming freshman class were low-income,” Peters wrote. “Admissions policies play a significant role in the racial and socioeconomic diversity of institutions, and plays a role in why many selective public universities are failing to enroll representative shares of low-income students and students of color relative to the racial and socioeconomic makeup of their states. U-M Ann Arbor should think critically about the equity implications of their admissions policies and focus on eradicating existing access and completion gaps on campus.”

However, Fitzgerald wrote the use of legacy status and the guaging of interest as it pertains to calls and visits are not factors in the University’s admissions process, though it is a common misconception that they do. He said the University does not give applicants preference in the admissions process if they have alumni relatives or are considered to be a legacy.

While the University does look at “demonstrated interest,” he wrote that it is not in terms of the number of visits or phone calls as some other colleges do. Rather, he wrote that is about the applicant’s demonstrated interest in their field of study, such as medical interest for Nursing applicants or musical experience for Music, Theatre & Dance applicants.

In general, Ariana Khan said she believes the added increase score further polarizes an already competitive environment.

“Universities strive for higher statistics,” Ariana Khan wrote. “The better the statistics, the better the perception of the University. For this reason, I believe universities select the highest-scoring students. The expectation to maintain the standard fosters competitiveness within the schools.”

LSA junior Cole Howe said he wasn’t nervous about applying to the university when he transferred from Grand Valley State University after his freshman year. However, he said he thinks some students looking to transfer may be deterred by University slogans like “Leaders and the Best.”

“It’s a prestigious school and tons of really good programs and I knew that it was like one of the best public schools in the country and the best school in the state for sure,” Howe said. “I could definitely see that (it may be daunting) for some people (coming to the University) thinking, ‘Oh, I’m not gonna fit in,’ and the whole imposter syndrome. I could definitely see that with things like ‘Leaders and the Best.’ Some people might be kind of scared off.”

During Howe’s application process, he said he was worried that even if he got in, he wouldn’t be able to afford it. However, he ended up receiving financial aid that lead to a similar price as the tuition he paid at GVSU. University programs like the Go Blue Guarantee are important to advertise, said Howe, to remove the fear of inaccessibility.

“When I told (my parents) I was applying here, at first, my dad didn’t even want me to come here because he was like, ‘Oh, it’s going to be too expensive,’” Howe said. “I can definitely see how a lot of people wouldn’t want to (come) because they think it’s going to be too expensive.”

This article has been updated with additional information from University spokesman Rick Fitzgerald regarding legacy status and demonstrated interest.

Return to clips