EEE outbreak prompts aerial spray

A portion of northern Washtenaw County was aerially sprayed to combat the spread of a mosquito-borne virus last Saturday night, according to Susan Ringler Cerniglia, Communications and Community Health Promotion Administrator at the Washtenaw County Health Department.

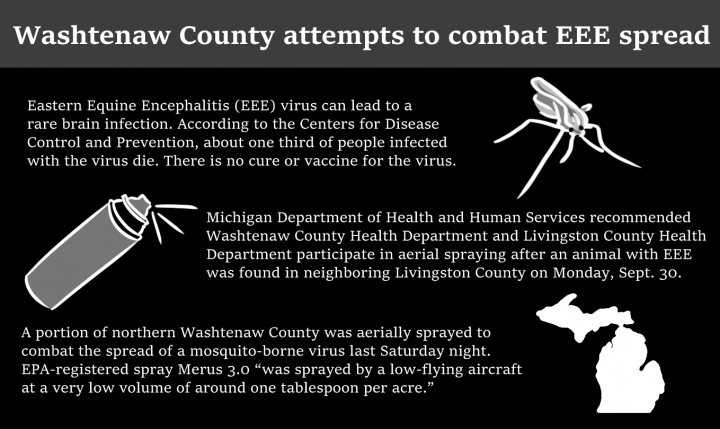

The decision to conduct aerial spraying came after the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services contacted WCHD on Sept. 29 about the spread of the virus called Eastern Equine Encephalitis. MDHHS recommended WCHD and Livingston County Health Department participate in aerial spraying after an animal with EEE was found in neighboring Livingston County on Monday, Sept. 30.

Cerniglia said WCHD was given short notice about the proposed spraying and ended up participating in the MDHHS-coordinated spraying.

“As a local health department, we have to prioritize reducing their risk of a potentially deadly infectious illness,” Cerniglia said.

When transmitted by mosquitoes to another organism, EEE can lead to a rare brain infection. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the virus is fatal to 30 percent of those infected. There is no cure or vaccine for the virus.

The CDC also noted areas of Michigan are increasingly at risk for EEE because of warmer weather. Nine people have been infected in Michigan, leading to three fatalities. Thirty animal cases of EEE have also been confirmed in 15 Michigan counties.

Joseph Eisenberg, professor and chair of the Department of Epidemiology at the School of Public Health, said the EEE virus is rare and part of a family of viruses, including West Nile and Saint Louis Encephalitis virus. He explained all three have been around for a while and pop up in different areas of the U.S.

Eisenberg mentioned the best way to combat EEE is through mosquito control and exposure as well as monitoring the host of the virus, birds, periodically as a warning system. He added monitoring whether there is viral activity in birds is challenging because of limited funding for rare viruses like EEE.

“We always want to make sure that we are minimizing mosquito exposure the best we can … and (using) mosquito repellent for individuals is one main thing from a public health perspective,” Eisenberg said.

LSA freshman Nayomie Allen, who is from St. Joseph County, said she was not aware of the EEE outbreak before talking to one of her family members. Allen said there was aerial spraying in her city after multiple animals with EEE were found. She added her family members were not aware of the planned spraying and believes residents should have been warned and offered an opportunity to opt-out.

“…I think they’re just trying to do what they could in the moment to prevent other people from getting it, so it was a good idea…but they should have probably sent out a warning,” Allen said.

WCHD posted a page on their website with information about how residents could opt-out of the spraying that took place last Saturday night. Cerniglia explained there would not have been any spraying if there were enough residents who opted out. She added the majority of the treatment area was in Livingston County, so WCHD did not hear from the neighboring county.

According to the website, the EPA-registered spray Merus 3.0 “was sprayed by a low-flying aircraft at a very low volume of around one tablespoon per acre.” Cerniglia added the spray has been used in other states and has shown to control mosquito populations effectively. She said its use in other states helped WCHD make the decision to participate in the aerial spraying.

Cerniglia also cited several concerns from residents about the potential ecological effects of the spray.

“The goal is to reduce the mosquito population,” Cerniglia said. “There’s been a lot of concern from other people based on bees and other animals that we don’t want to kill off, and, of course, we would never want to do anything that was potentially harmful to people. It’s really important to understand the way it’s being applied.”

When asked about his opinion on the aerial spraying, Eisenberg said the benefits outweigh the costs. He added the spraying could minimize the risks associated with transmission, especially because the mosquitoes could also be transmitting the West Nile virus.

“In the context that we now have an outbreak that is actually killing people, I think that the spraying is warranted,” Eisenberg said. “It’s not necessarily warranted as a preventive measure in the future when we don’t have an outbreak.”

Cerniglia explained some of the concerns from residents may stem from mistrust.

“No doubt, there’s a lot of concern and really what fuels into that is mistrust and, you know, even though we may be able to provide some of this information, people don’t necessarily believe it or trust it,” Cerniglia said.

Cerniglia said the short notice from MDHHS made it difficult to schedule a community meeting, but there was a meeting addressing EEE virus on Oct. 3 in Webster Township.

Cerniglia mentioned residents were concerned about the lack of notice even though her office “actively shared” new information once they received it. She added WCHD posted updated EEE virus information on their website, press releases and sent information to commissioners, but she emphasized it’s a challenge to directly reach every resident in the current information environment.

“We’re committed to listening to people and talking through it, but unfortunately, we had to make this difficult decision and we do hope … we can kind of open dialogue with community members and other organizations about this type of response, which is considered (an) emergency response,” she said.

Cerniglia said WCHD will be on the lookout for any additional EEE cases that may warrant another aerial spraying.

Eisenberg mentioned a program focused on killing mosquito larvae would be most beneficial to prevent another outbreak of a mosquito-borne disease.

Cerniglia said WCHD will look into integrated mosquito control programs, which occur in other parts of the U.S. so that there is a less likely chance for emergency responses like this one.

“That may be an investment that local communities, as well as the state, can re-look at and prioritize, especially if there’s concern about the changing climate and if this type of infectious problem may occur,” Cerniglia said.