Michigan law exacerbated city water problems in minority, low-income cities, U-M study finds

Residents in Hamtramck, Mich., lined up to receive water filters at the Hamtramck Town Center last Thursday after city officials found high levels of lead in the city drinking water last Wednesday. Other Michigan cities, including Flint and Benton Harbor, have experienced similar issues with their drinking water.

A new study published last month from the University of Michigan suggests that cities like Hamtramck — predominantly with low-income and minority residents — may be experiencing issues with their water systems because they have been put under emergency financial management.

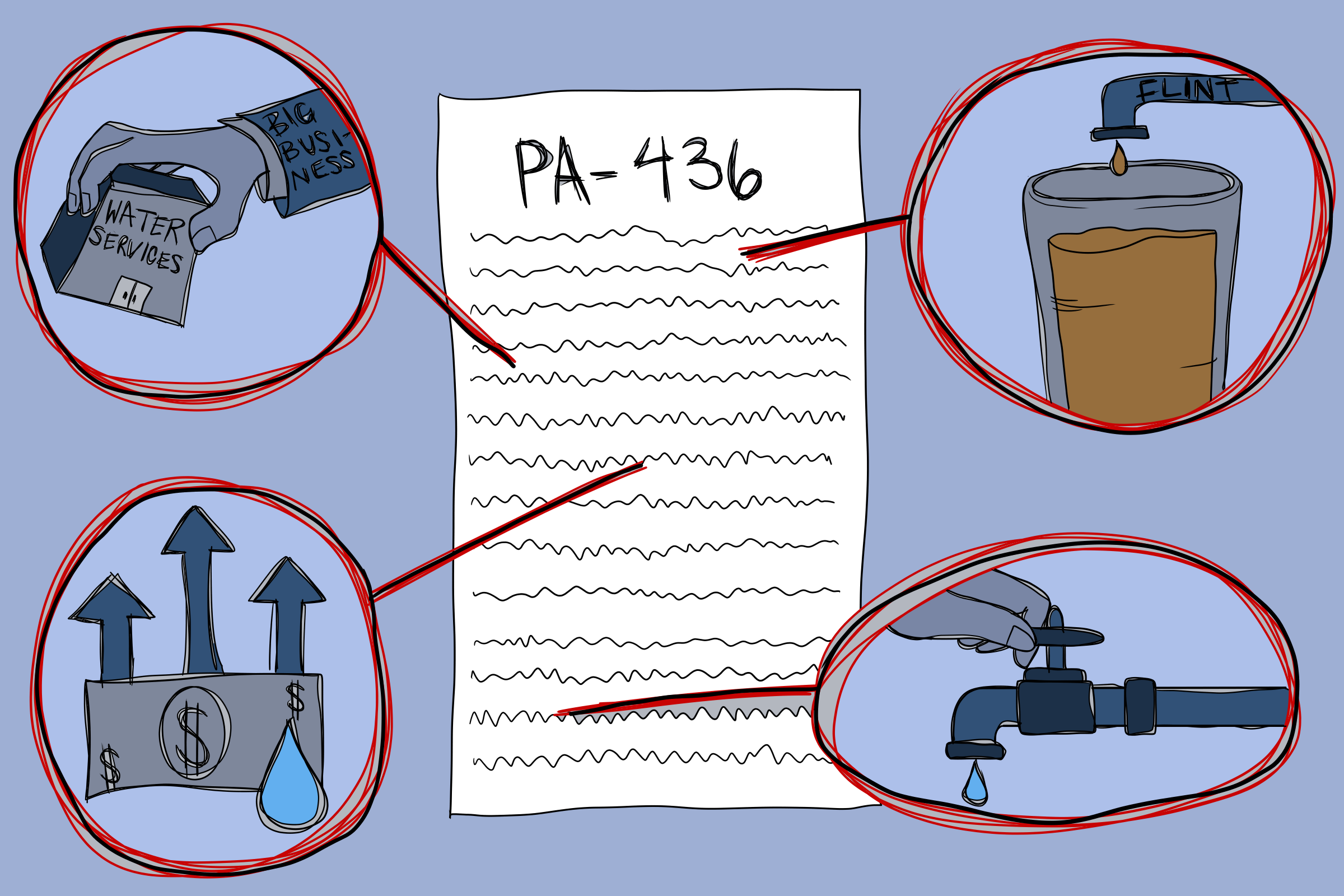

Public Act 436, also known as the emergency manager law, was passed in 2012 by the Michigan state legislature to provide support for financially distressed Michigan cities through implementing an emergency management system. Under the emergency management system, a city receives an emergency manager to resolve financial issues.

Sara Hughes, assistant professor of environment and sustainability, co-wrote the recent study and said that under the law, emergency managers have the power to override local elected officials.

“An emergency manager sometimes overrides the preferences of the city council,” Hughes said. “When you’re under emergency management, the emergency manager trumps city council and the mayor. The emergency manager is the boss.”

Anna Kopec, a graduate student at the University of Toronto, collaborated on the study and noted that defining which cities are financially distressed is difficult and ambiguous.

“Not only is the law not being applied in the way that it’s saying it’s supposed to be applied, but the discretionary power that it has impacts democracy and the services that residents receive,” Kopec said. “Legislation is meant to keep things objective, but it definitely doesn’t happen that way.”

Eleven cities have been put under emergency management, including Flint, Highland Park, Benton Harbor, Hamtramck and Detroit, among others. Residents of Flint experienced mismanagement of their water system in 2014 when their emergency manager, Ed Kurtz, decided to switch Flint’s water source to the Flint River. After the shift, improper treatment of the water led to lead-tainted water.

Groups like the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan have challenged PA 436 in court, arguing that it disenfranchises people of color; however, their legal argument has been dismissed by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals and a lower court.

Hughes said her research group wanted to address the validity of the legal arguments made by these groups by looking at how an emergency manager may affect public services in a community.

“Lawyers and activists have been trying to show that the law was being applied unevenly and disproportionately harming Black communities and low-income communities,” Hughes said. “The evidence they were using was compelling, but not complete.”

The research group first compared the financial health of the 11 cities that were placed under emergency management control to other cities in Michigan. They found that the cities under emergency control were not the most financially strained cities in Michigan, suggesting that the cities were selected to be put under emergency management for other reasons, like the racial makeup and socioeconomic status of the city.

The Michigan Civil Rights Department also found that racism was a factor in the emergency management of Flint. The organization’s report concluded that PA 436 should be rewritten and state officials should attend implicit bias training.

“While municipal takeover policies are often presented by supporters as rationalized, apolitical and technocratic responses to municipal financial distress, they have been found to in fact be deeply biased and often racialized responses to the structural challenges facing many U.S. cities,” the University of Michigan study reads.

Aidan Leach, College of Arts & Sciences sophomore at University of Michigan-Flint, lives in the Flint area and said he has seen some city officials perpetuate inequities in the community.

“Every opportunity that comes around, people in power put already disadvantaged groups of people further into the dirt,” Leach said. “After a while, you start to think, ‘Maybe this isn’t just a coincidence. Maybe it’s happening on purpose.’ And it is.”

Kopec mentioned she was not surprised that minority and low socioeconomic cities were targeted by this law. She hopes the results will be used to change policy.

“In some ways, it’s heartbreaking to (learn about these inequalities),” Kopec said. “But it’s also beneficial to think about the policy and legislative changes that may occur.”

Although the researchers did not explore racial biases, Hughes emphasized that more affluent and primarily white communities like Ann Arbor likely wouldn’t experience emergency management.

“The state might have more confidence that with a little time and a little breathing room, a community like Ann Arbor could find its way out of (financial distress) on its own,” Hughes said. “But for a city like Benton Harbor, Flint or Hamtramck, the state might feel less confident in them.”

Business sophomore Rita Brooks, who is part of the Flint Justice Partnership and works with residents of Flint, said she was not surprised by the study’s findings. She highlighted that minority and low socioeconomic cities have been historically under-resourced.

“This state and this country has a history of making decisions based on race that leads to racial disparities,” Brooks said. “It’s unfortunate that to this day people are still being discriminated against and experiencing environmental racism because of factors that are outside of their control.”

In the study, modifications to drinking water systems, including privatization, water rate increases and water shutoffs for nonpayment, were observed in six of the 11 cities that came under emergency management. Hughes noted that these changes were not seen in financially distressed cities that weren’t under emergency management.

“Changes made to the drinking water systems is something you would expect under emergency management when you’re trying to raise revenue and cut budgets,” Hughes said. “We couldn’t find any evidence that (the non-emergency management cities) had had similar types of changes.”

The group also found that when cities came under emergency management, they lost state funding, while other cities saw a funding increase. Hughes explained that this worsened the financial situation of cities under emergency management control.

“These emergency manager cities were getting budget cuts and, at the same time, they were getting a revenue squeeze,” Hughes said. “This was a really tough position for these cities to be in.”

Hughes said she hopes the study will be used by policymakers to avoid more water mismanagement incidents. She added that the study could revitalize the conversation around PA 436.

“Michigan is on one end of the spectrum compared to other states in terms of how it intervenes during times of municipal financial distress,” Hughes said. “We can change this relationship between the state and the cities on this issue in ways that would really benefit communities.”