Podcast episode: Reimagining epilepsy care with food

Kristin Squires’ four-year-old son was put on his fourth medication three months after being diagnosed with a rare form of epilepsy.

“It was difficult (to watch) our child completely disappear,” Squires said in an interview with us. “He was no longer this person that we’d raised for four and a half years. He was gone.”

Epilepsy is a seizure disorder that affects about 3.4 million Americans. It is characterized by abnormal or hyperactive brain cell activity. Although the cause of epilepsy is not always known, certain forms of epilepsy are linked to genetic disorders, stroke, infection, and brain injury.

When Squires’ son, Graham Squires, experiences a seizure, he exhibits atypical symptoms, behavior, and sensations. When some of these symptoms are experienced simultaneously, Graham loses consciousness. Although the disease oftentimes cannot be cured, epilepsy is most commonly treated with medications, which reduce the probability of having a seizure.

However, anti-seizure medications don’t work for everyone. A study published in 2000 found that about 30% of patients with epilepsy — including Graham — are unable to adequately control their seizures with medications. In addition, about 16% of patients experience side effects from anti-seizure drugs, which Graham also encountered.

“Everything was going so quickly downhill,” Kristin said. “At that point, we were begging to start keto.”

The ketogenic diet, commonly referred to as keto, is a supplemental treatment most commonly offered to epilepsy patients – both kids and adults – who do not improve with anti-seizure drugs. The low-carb, high-fat diet has been extensively studied and was first reported as an epilepsy treatment by the Greek physician Hippocrates over 2,420 years ago.

When patients begin the keto diet, their body is tricked into a fasting state. This causes their body to use fats, instead of carbs, as the primary fuel source. This process is called ketosis and it leads to the formation of ketones, which are used as fuel sources for the body.

In the past two decades, the diet has exploded in popularity and scientists have studied the potential benefits of keto. Detlev Boison, professor of neurosurgery at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, is one of those scientists.

“Epilepsy is a complex syndrome,” Boison said in an interview with us. “It cannot be treated by a single drug. It needs to be treated by several mechanisms that all work hand in hand.”

Unlike pseudo-miracle food cures shared on social media, researchers like Boison have demonstrated that the once-controversial keto diet improves health outcomes for adults and children with epilepsy. The first randomized, controlled study published in 2008 found that seizure frequency significantly decreased in 38% of the patients on the diet. Although many patients adopt the diet after trying other treatments, patients remain on their anti-seizure medications while on the diet.

Despite research on epilepsy and the diet, scientists are still unsure how the diet delivers these impressive results. Although some in the field disagree with Boison, he believes that the diet may influence when certain genes are accessible to cells.

“It almost sounds like fantasy,” he said.

But he’s not alone. One mouse study in 2018 found that the keto diet alters which genes are accessible to cells. The researchers proposed that a certain type of ketone – called beta-hydroxybutyrate or BHB – can affect processes that turn certain genes on and off depending on metabolic needs. The genes affected by this mechanism are involved in fat and sugar metabolism. In a study from 2020, researchers found similar results in human cells, which also produce the BHB ketone.

Though Boison said these results are preliminary and more research needs to be conducted, many patients on the keto diet have seen positive results. Studies have found that seizures may be significantly reduced 10 weeks or even immediately after starting the diet. If a patient’s seizures are well-controlled after about two years, some patients are taken off the diet.

The mother of a three-year-old with epilepsy told us in an interview that she noticed a drastic improvement in her son’s health after he began the diet. The mom requested anonymity to protect her privacy and will be referred to by her first name, Sylwia.

“Within a week, he was a normal child again,” Sylwia said. “There were no side effects.”

Kristin’s husband, Mark Squires, noticed a similar change. Mark noted that Graham’s symptoms and developmental milestones improved.

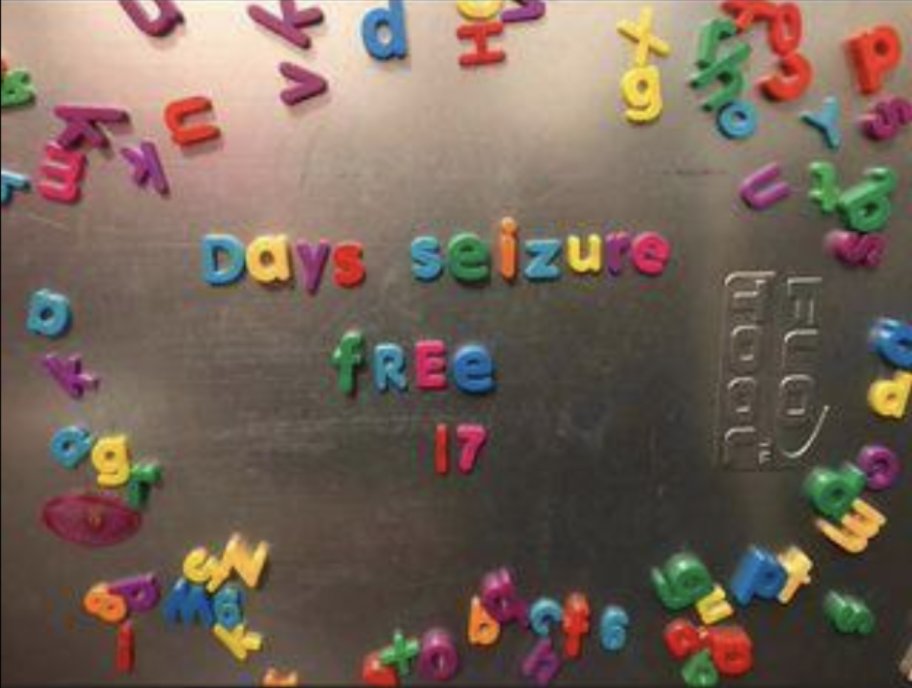

“As soon as we were on the diet, all seizures were gone,” Mark said.

Even though there are more serious side effects associated with anti-seizure medications, the diet can be dangerous, according to Samantha Choi.

“We have a very close monitoring process,” Choi, a keto diet dietitian at Michigan Medicine, said in an interview with us. “We monitor (patients’) blood every three months and recommend urine analysis annually … so our team has very strong guidelines.”

According to Eric Kossoff, professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, more hospitals offer the diet as a treatment option for patients. He estimated that only about 100 hospitals in the U.S. offered the treatment in 2010, compared to about 1,000 hospitals in 2022. The treatment has also spread to over 50 countries.

However, some epilepsy patients, including 36-year-old Laurissa Clarke, do not have access to a local hospital that offers a keto diet treatment. Clarke, who lives in rural Canada, relies on telehealth visits with her neurologist, who is a 38-hour drive away.

“My neurologist is actually in Ontario,” Clarke said in an interview with us. “My doctor appointments are like this (Zoom interview). We meet over video.”

Patients on the diet can also face financial difficulties. It can cost upwards of $500 to begin the keto diet. Once started, patients go through a lengthy onboarding process, laboratory studies, and are required to use keto diet supplements and high-fat foods. According to Choi, most insurance companies cover these expenses.

But Kristin and Mark experienced issues with their insurance company. Kristin noted that some of the supplements they purchased for Graham were not covered by insurance.

“Some kids are on eight medications before they even get to attempt keto,” Kristin said. “(Insurance companies) are not willing to put forward some of the money to (start) keto, which probably would be cheaper (and more effective) than medications.”

While the keto diet has risen to fame as one of the most popular diets in the U.S., Choi’s co-worker at Michigan Medicine, Rebecca Thorwall, told us in an interview that the mainstream keto diet is not equivalent to the meticulously-calculated diet prescribed by her team.

“More people are familiar with the concept of a ketogenic diet,” Thorwall said. “But it does kind of lead to a lot more confusion about what actually is the ketogenic diet and what is inappropriate food.”

Thorwall’s observation translates to some of the dropout rates seen in clinical trials. Compared to a typical American diet that includes 200-300 grams of carbohydrates per day, a patient on keto may be restricted to about 10-15 grams per day, which is equivalent to about one orange. In one study published last year, about 30% of patients discontinued the diet for various reasons. For example, Choi mentioned that some patients find the diet too inflexible. Because of the restrictive nature of keto, modified diets like Atkins may be more suitable for certain patients. In fact, studies have shown that a modified Atkins diet may be as effective as keto.

Though Graham’s symptoms dramatically improved, Kristin and Mark emphasized that the transition to keto wasn’t easy. For example, they were required to use a keto diet calculator to determine Graham’s optimal food intake. In spite of the challenges, Mark recommends families try the diet.

“You have to try it,” Mark said. “It doesn’t always work for everyone, but … if you want to do every single possible thing that you can for your child, you have to at least try it.”

The mother of Anders, an 11-year-old who has been on the diet for five years to treat his epilepsy, told us in an interview that she also struggled with her son’s adjustment. She mentioned that Anders experienced brain fog – also called keto flu. As a result, she and her husband decided to begin the diet, too. The mom requested anonymity for herself and Anders to protect their privacy. They will be referred to by their first names, Lauren and Anders.

“The first month felt like I was killing my child,” Lauren said. “He was so tired and just kind of figuring out all the things.”

In addition to their rocky start, Kristin said she struggled with holidays like Halloween, which come with temptations. Kristin emphasized that if Graham were to eat Halloween candy, which is prohibited from the regimen, seizures could return.

Because of this, parents like Lauren have created their own traditions.

“On Halloween, we do a switch witch,” Lauren said. “I’ll make a treat that is keto and then both of my children will trade in all of their candy for Pokémon cards.”

Despite the expansion in access to the diet, all of the patients we spoke to said that they were the ones proposing keto as a treatment option — not their physicians. Many families, including Sylwia’s, learned about the diet on Facebook.

Although everyone we spoke to turned to certified keto dieticians and neurologists, Facebook is a breeding ground for medical misinformation. That’s why Boison said the medical community should develop an education platform for clinicians and the public.

Thorwall agrees with Boison. She said more research is needed to make individuals aware of the diet.

“It’s well worth giving up candy and cookies so that they can have a completely different life,” Thorwall said. “I really love this diet and I feel very passionately about what we do. We’re very lucky to get to work with these families.”

All of the patients and families we interviewed hope that awareness about the diet increases. Although the transition to keto was difficult, Kristin said that support from patients and fellow parents made the journey easier.

“As a family, (the process) is incredibly overwhelming,” Kristin said. “It is hard. It is a lot of work. But for us, it was harder to watch the side effects take our son away. I would much rather spend the time in the kitchen and the headache of putting things into the keto calculator to get rid of the side effects and watch our son come back. We never thought we’d be here. He’s doing amazing.”

We would like to thank the families and patients we interviewed for this article. The stories shared do not represent all of the unique challenges individuals with epilepsy face. Some patients don’t improve on the diet — but many do. Although there is more work to be done in the field, we hope this article serves as a non-biased starting point for professionals and patients interested in how the diet may affect individuals with epilepsy. Both of us became fascinated by how food could be used to treat epilepsy, and we cannot wait to learn more about how this treatment impacts patients in the future.

If you are interested in learning more about this topic, visit The Charlie Foundation or Matthew’s Friends. If you would like to implement keto into your treatment plan, please reach out to a healthcare professional.